|

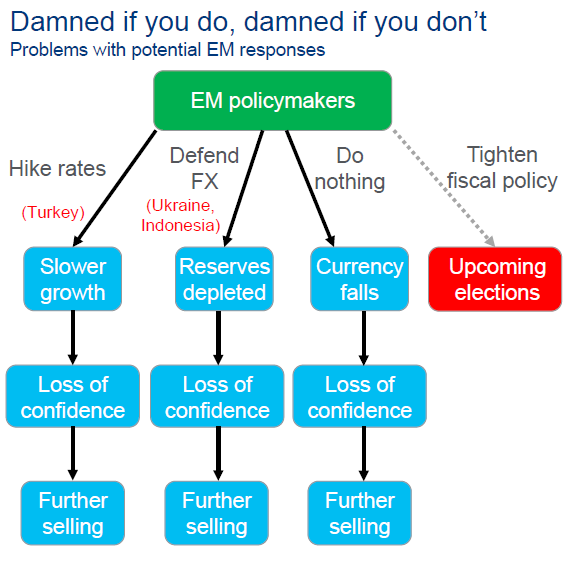

| source: Citicorp; Financial Times |

The latest weekly piece from global strategist Michael Harnett at Merrill Lynch highlights the bullish sentiment surrounding European stocks.

According to his data, European equity funds have received inflows of $12 billion over the past two months, one of the highest levels on record.This is even more impressive when you consider that the investment surge is occurring at the end of August, traditionally one of the slowest times for investing during the year.

Meanwhile, sentiment around the emerging markets (EM) stocks remains decidedly bearish. Nearly $4 billion flowed out from EM funds last week, according to Merrill, which is the largest outflow over the past 9 weeks.

Investors are clearly worried that we are seeing a replay of the 1998 EM meltdown, even though many observers insist that "this time is different".

Paul Krugman in this morning's New York Times, for example, thinks that we should be more worried about the European peripheral countries like Greece instead of Indonesia. While the fundamentals may suggest that the problems are containable, he thinks that government responses may make the situation considerably worse:

Consider, for example, the worst-case nation during each crisis: Indonesia then, Greece now.

Indonesia’s slump, which saw the economy contract 13 percent in 1998,

was a terrible thing. But a solid recovery was under way by 2000. By

2003, Indonesia’s economy had passed its precrisis peak; as of last

year, it was 72 percent larger than it was in 1997.

Now compare this with Greece, where output is down

more than 20 percent since 2007 and is still falling fast. Nobody knows

when recovery will begin, and my guess is that few observers expect to

see the Greek economy recover to precrisis levels this decade.

Why are things so much worse this time? One answer is that Indonesia had

its own currency, and the slide in the rupiah was, eventually, a very

good thing. Meanwhile, Greece is trapped in the euro. In addition,

however, policy makers were more flexible in the ’90s than they are

today. The International Monetary Fund initially demanded tough

austerity policies in Asia, but it soon reversed course.

This time, the demands placed on Greece and other debtors have been

relentlessly harsh, and the more austerity fails, the more bloodletting

is demanded.

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/08/30/opinion/krugman-the-unsaved-world.html?ref=opinion

Predictably, perhaps, Ambrose Evans-Pritchard of the London Telegraph thinks that the world's monetary authorities are underestimating the dangers of the current EM situation.

He notes that most have focused where Professor Krugman is; namely, the much healthier currency reserves, and less foreign debt exposure, of most of the EM countries.

However, as EM countries seek to mitigate some of impact of the reversal of the global capital flows it enjoyed over the past few years, the potential for serious policy misstep is high:

This has the makings of a grave policy error: a repeat of the dramatic events

in the autumn of 1998 at best; a full-blown debacle and a slide into a

second leg of the Long Slump at worst.

Emerging markets are now big enough to drag down the global economy. As

Indonesia, India, Ukraine, Brazil, Turkey, Venezuela, South Africa, Russia,

Thailand and Kazakhstan try to shore up their currencies, the effect is

ricocheting back into the advanced world in higher borrowing costs. Even

China felt compelled to sell $20bn of US Treasuries in July.

"They are running down reserves by selling US and European bonds, leading to a

self-reinforcing feedback loop," said Simon Derrick from BNY Mellon.

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/comment/ambroseevans_pritchard/10272285/Emerging-market-rout-is-too-big-for-the-Fed-to-ignore.html

The problem as I see it is best captured by the chart shown above, courtesy of strategists at Citigroup by way of the Financial Times.

The resources are available to China, Brazil, et. al. to contain the impact of market sentiment. The problem is whether the local political sentiment is sufficient to ask its populace to face difficult economic times to appease the currency markets.

So are the EM stocks now a bargain?

Writing in this morning's Financial Times, here's what columnist James Mackintosh noted:

Emerging markets are not one of those screaming bargains...

EM equities have not even had a one-fifth fall from their peak this year. In dollar terms they are off 16 per cent; in local currency terms they are down less than a tenth.

But in relative terms EM shares look like a steal. They have lagged behind developed market shares in the past three years in a way reminiscent of the aftermath of Lehman's collapse, the 1997 Asian crisis, or the reaction to the 1994 rate rises.

The valuation discount to developed markets has not been as big since 2005 (on a price-to-book value) or 2006 (for price to forward earnings.

http://www.ft.com/home/us

I think Mackintosh has got the situation right: EM stocks look cheap, but they could get even more attractive as the true impact of the Great Global Unwind become more evident.

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/comment/ambroseevans_pritchard/10272285/Emerging-market-rout-is-too-big-for-the-Fed-to-ignore.html

The problem as I see it is best captured by the chart shown above, courtesy of strategists at Citigroup by way of the Financial Times.

The resources are available to China, Brazil, et. al. to contain the impact of market sentiment. The problem is whether the local political sentiment is sufficient to ask its populace to face difficult economic times to appease the currency markets.

So are the EM stocks now a bargain?

Writing in this morning's Financial Times, here's what columnist James Mackintosh noted:

Emerging markets are not one of those screaming bargains...

EM equities have not even had a one-fifth fall from their peak this year. In dollar terms they are off 16 per cent; in local currency terms they are down less than a tenth.

But in relative terms EM shares look like a steal. They have lagged behind developed market shares in the past three years in a way reminiscent of the aftermath of Lehman's collapse, the 1997 Asian crisis, or the reaction to the 1994 rate rises.

The valuation discount to developed markets has not been as big since 2005 (on a price-to-book value) or 2006 (for price to forward earnings.

http://www.ft.com/home/us

I think Mackintosh has got the situation right: EM stocks look cheap, but they could get even more attractive as the true impact of the Great Global Unwind become more evident.